Regional Mobility Patterns: Finding Insight Through the Canadian Census

Regional mobility patterns in a city can provide important clues as to where jobs, population and economic activity is concentrating — all important indicators for real estate investors.

The latest numbers on commuting via the 2016 census accordingly highlight some interesting trends related to mobility patterns across major Canadian cities. Commuting patterns can impact the demand, design and location of a variety of asset classes. Transit access remains important for multi-family and office property, and increasingly industrial as well. Aside from location, commuting patterns can also impact the provision and demand for amenities such as parking, car-sharing or end-of trip facilities.

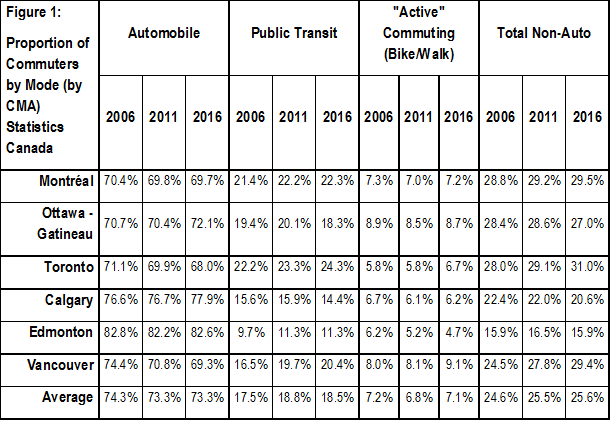

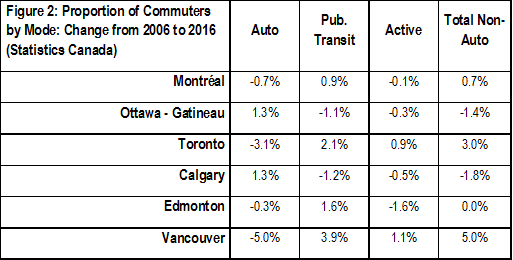

Looking at average daily commuting trips (Fig. 1) by mode of transportation for the six largest census metropolitan areas (CMAs) in Canada, we can see that automobiles still account for the dominant share of travel at 73.3% on average. However, when we compare the change (Fig. 2) in the share of automobile trips between 2006 and 2016 census years notable trends emerge. For instance, Ottawa and Calgary actually increased its regional share of automobile use by 1.3%, compared to Montreal and Edmonton which stayed mostly unchanged the last decade. Interestingly, Toronto and Vancouver witnessed notable declines in automobile use at – 3.1% and -5.0% respectively.

The change in public transit use and active (walking and biking) transportation over time is probably a more compelling indicator to look at from a real estate perspective. Most cities continue to embrace smart growth and transit-oriented development (TOD) policies—higher rates of non-auto commuting is a good measure for whether or not policy objectives and regional growth strategies are actually working.

Vancouver witnessed the largest ten-year shift. Regional transit use has increased by 3.9% with active transportation up 1.1%. Overall, non-auto trips increased by 5% the last decade. While this may seem like a small gain, a 5% shift in commuting patterns for population of 2.5 million people results in approximately 125,000 more people walking, biking or transiting to work. If we look at Toronto with a 3% increase in non-auto trips, the shift totals 181,000 people[1].

The increase in non-auto commuting rates in Vancouver and Toronto are unsurprising given fairly significant transit investments in those cities, include the completion of the Canada Rapid Transit Line in Vancouver and ongoing improvements to the Toronto Transit Commission System. However, there has also been sizable transit investment in cities where non-auto commuting rates declined—new light rail stations and capacity have also been added in Montreal, and particularly in Calgary and Ottawa. This suggests other factors drive transit-use beyond supply alone.

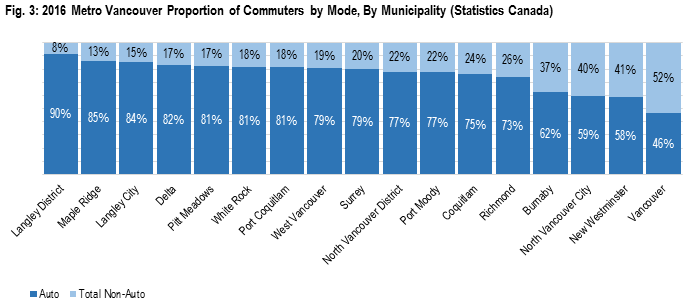

Looking within Vancouver and Toronto specifically, we see interesting patterns. For Metro Vancouver (Figure 3), four municipalities (Burnaby, City of North Vancouver, New Westminster and Vancouver) in the region have more than a third of its population taking non-auto commuting trips to work. Unsurprisingly, these cities are the closest to the downtown core with substantial bus and rapid transit access. The remaining cities in Figure 3 are more or less suburban communities. The City of Vancouver notably has more people taking alternative forms of transportation than driving according to the census.

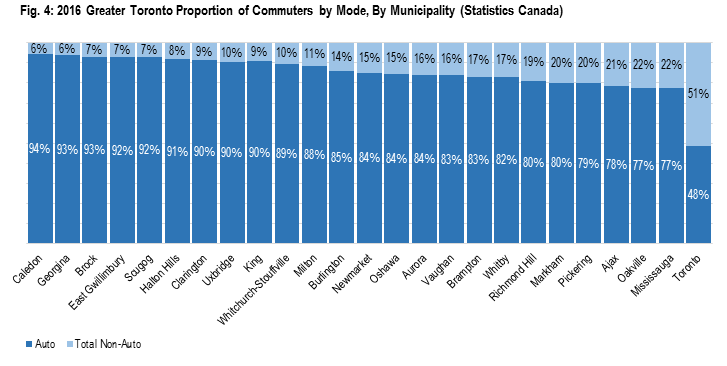

When we look at the Greater Toronto Area (Figure 4), similar patterns emerge. Most suburban municipalities are still auto-oriented, with the City of Toronto commanding a near 50/50 split between auto and non-auto commutes. While the data for the Greater Toronto Area appears to contrast Metro Vancouver in the sense that it has one city that has a significantly higher share of non-auto commuting than the rest, note that the City of Toronto’s land area is larger than Burnaby, City of North Vancouver, New Westminster and Vancouver combined. This generally suggests that non-auto use is rising in areas closest to the urban cores.

So what do the findings tell us from a real estate perspective?

It suggests that not all cities progress the same in terms of density and transit use with some meeting regional growth targets better than others. For investors, this provides clues as to which cities—and what areas—have higher TOD and mixed-use development potential than others. From a design perspective, some developments may benefit from reduced parking requirements in exchange for promoting alternative transportation options.

[1] The commuting results are based off a statistically significant sample survey conducted by Statistics Canada as part of the 5-year census and serves as a proxy for the overall population.

Based in Vancouver, Anthio brings more than 15 years of experience to GWLRA’s Research and Strategy team specializing in property market analysis, applied research and portfolio strategy. He has a Master’s in Urban Planning and Development from the University of Toronto.